by Luca Govoni

The Tang, Song and Ming dynasties, Confucius, the Yellow Emperor, Pharmacopoeia: testimonies over the centuries that certify oenology in the Orient.

“Therein is much wine, and in all the province of Cattai there is no wine except in these cities; and this supplies all the surrounding provinces”: so reported the Venetian Marco Polo in Il Milione. This is the sole explicit reference in the opus regarding the production of wine from grapes in all the great China. The famous explorer leads us to the land of Cathay, the northern part of the Celestial Empire and destination of his long wanderings. Nor could the monks Giovanni from Pian del Carpine and friar Guglielmo of Rubruk, who travelled to the Orient before Marco Polo, testify to the presence of the sacred drink.

But while it is known that grapes were cultivated and wine made in northern China, it is also true that the history of oenology in the Orient leaves room for discrepancies, with theories and hypotheses of varying degrees of plausibility attesting to its arrival in the centuries before Christ, and its subsequent spreading.

How can we not wonder when vitis vinifera made it to the Orient? What habits, techniques and procedures were in use; what intrinsic properties were attributed to the nectar of the gods? The questions are multiplying, but the questions that arise legitimize all doubt. The historical reconstruction of the presence of vines and wine is firstly undermined by the linguistic difficulties and by the translation itself of the word wine.

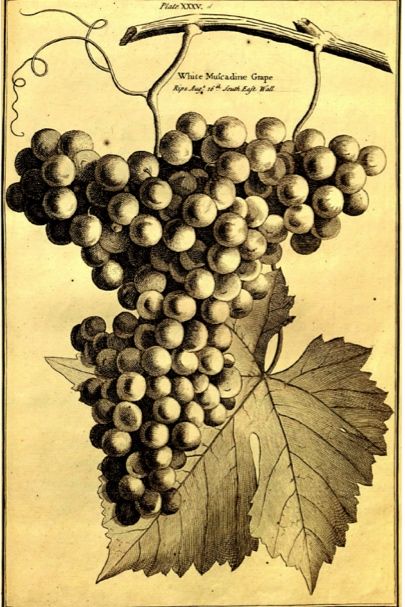

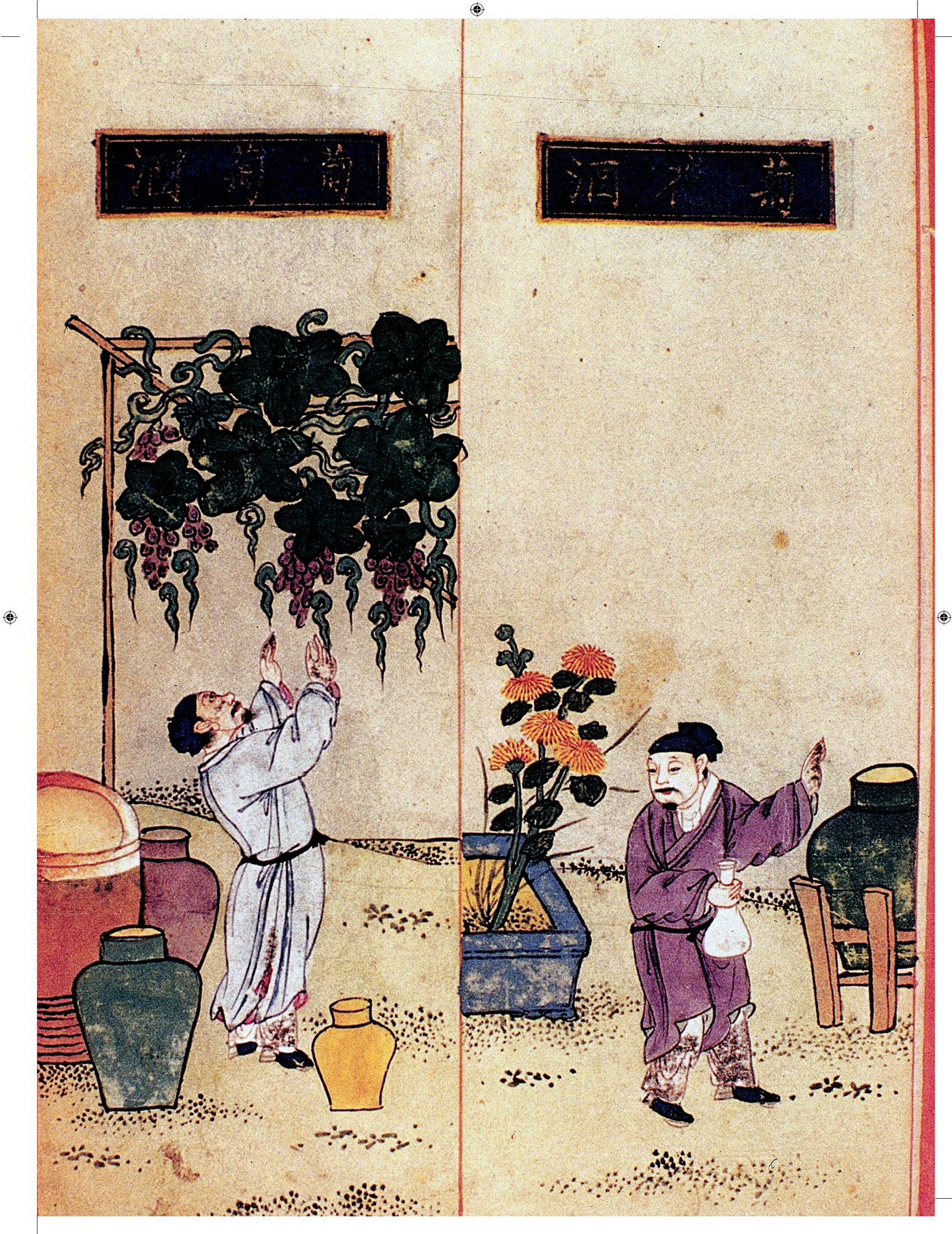

In Chinese, the term wine has in- discriminately indicated any drink made by fermenting fruit. This is attested by a document from the Tang dynasty (VII-X century), which says “you can ferment cow's milk, soya and berries and other things too to make wine”. Complicating matters is another work dating from the same dynasty titled The Song of the Grape, whose verses in honour of the grape named ‘mare’s nipples’ recited thus: “...the flowers open like silk fringes, the fruits hang like bunches of pearls... We men of Zin cultivate these grapes like rarest jewels and from them we make a delicious wine that men ever thirst for.”

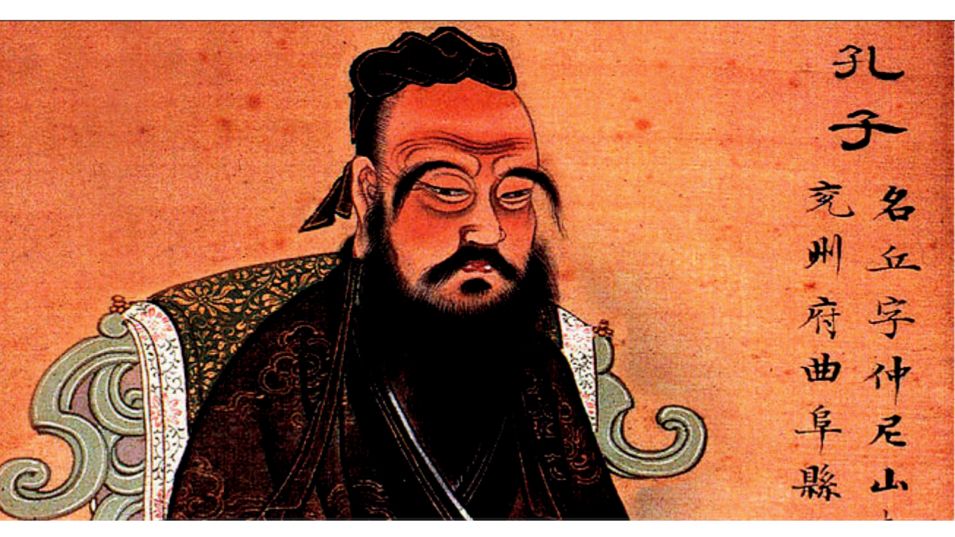

The same story is repeating today in the everydayness of a traditional Chinese lunch accompanied by so-called ‘wine’, a kind of fortified wine made from a mixture of plain rice, millet, water and enzymes, brought to a temperature of 70°C and then served hot, perhaps aged for forty years. And if the language barrier may seem the first great obstacle, no less intimidating is the complex mass of texts gathering quotations, references, condemnations and approvals of wine made from grapes and its medicinal properties. Suffice it to think of the warning issued by the great Koˇng Fu¯zıˇ; that is, the thinker and philosopher Confu-cius, who said “Embrace wine if you will, but do not drink it to intoxication”, marking again that weight of inestimable appeal that wine exercises with its essence; but in the end per-haps he was referring to the intoxicating and ephemeral power of other beverages produced by fermenting various fruits.

Ancient Chinese mythology indicates three characters, unique among their kind, that incarnate the evolution of an agro-forestry-pastoral model similar to that which occurred in the western world in the 2nd-5th centuries AD, the result of the merg-er between the barbarian dietary model and the Greco-Roman one.

In ancient China there lived Fu Hsi the hunter, Shen Nung the peasant and Huang Ti the farmer. The first is associated with the activities of hunting and fishing, and he is attributed with the invention of cooking. Shen Nung is the Divine Peasant, credited with inventing the plough, the hoe, and the keeping of domestic animals. Also called the emperor of the five cereals, he is the first figure to testify, albeit in a fairy tale manner, to the presence of wine in the country. In his texts he wrote that “grapes can be used for making wine”, and that the grape itself “is good for muscles and bones, strengthens the vital flow, builds resistance to hunger, immunity to colds, and if taken for a long time is slimming, keeps old age at bay and rejuvenates”.

Lastly, the third persona, Huang Ti, also called the Yellow Emperor and still worshipped today as the patron saint of Taoism, is credited with culti-vating grain, and inventing the mortar and pestle. Subsequently, Chi-nese pharmacopoeia offers several suggestions on the subject of wine, also specifying that it be wine from grapes and not from other fruits. This is the case with the famous Shih Liao Pên Ts’ao, translatable as Text on dietetics, by doctor Mêng Shên dating from the 11th century AD.

Here, grape juice is celebrated, saying “if a pregnant woman be oppressed by her baby agitating against her heart, drinking a root decoction will lower the uterus and bring relief”, and “add grapes to wine and drink it during epidemics to avoid sores and abscesses”. In the encyclopaedic Essential Medical Matters (Pên T’sao P’in Hui Ching Yao), an ancient Chinese pharmacological codex in 42 books by Liu Wen-t’ai, there are several recommendations about wine and grapes. For example: “in the circulation of flows, fruit heals dropsy, regulates and harnesses flows and makes urine”; and “add roasted salt to wine and drink it; it will stop bleeding of wounds from veins and arteries.”

In short, wine seemed to have regenerative properties for the lungs and the intestine, and was also considered an excellent remedy for cholera and various epidemics. In his book Medicine in China. A History of Phar-maceutics, Paul U. Unschuld, Director of the Institute for the History of Medicine at Munich University, also mentions references to another fun-damental text of Chinese medical culture, Memoirs of Famous Doctors by T’ao Hung-Ching, which relates how “wine from grapes benefits the breath of life and makes it more harmonious, more resistant in famines, and strengthens the will. Spring wine fattens and makes the skin clearer.” Medical issues aside, we must wait until the Song dynasty (10th-13th centuries) for mention of evolution regarding wine, and the Ming dynas-ty (14th-17th centuries) which made room for the expansion of a wine market and oenological science.

In fact, the 16th century saw the publi-cation of the Text on Agronomy by Xu Guangqi from Shanghai, defined by the Jesuit Matteo Ricci of Macerata as a scholar “of fine genius and great natural virtues”. He, an astronomer, mathematician and high of-ficer of the empire who lived at the end of the Ming dynasty, is known as the beneficent father of his country also for spreading new technologies in farming. In his essay on agriculture Nong Zheng Quan Shu, published in 1639, he describes the types of vines and grapes present in his region, clas-sifying and analysing them in detail. Then again, some wild vines such as vitis davidii, lanata, thumbergii, amurensis, and flexuosa, many of which are still found in the Orient, are varieties in use of which little is known at the historical and archae-ological level. And respecting ancient Chinese medical doctrines is not enough to fill the gaps in a detailed and precise study of the education on wine and the Dyonisian fervour of the West.

We need facts. Such as the account of the expedition of the Chinese general Chang Chien to Fergana, east of Samarkand, in 128 BC, in order to deal with matters relating to the famous intercontinental silk trading route. The general, an Imperial emissary during the period of the Han dynasty, who was considered the first official diplomat and a national hero for the key role he played in the opening of China to international trade, procured the seeds of the vitis vinifera and of the medicinal herb to bring them as gifts on his return to his emperor, finally documenting the date of entry of the first vine that was cultivated in the Celestial Empire.