by Pierluigi Gorgoni photos by Ugo Zamborlini

He made Piedmont wine famous around the world and is the top international representative of Italian expertise in the vineyard, and it is all thanks to his contagious energy and his experience. Angelo Gaja tells his tale.

As I approached Barbaresco to meet Angelo Gaja, my thoughts turned (as often happens, though rarely so sharply) to Gino Ve- ronelli. He came to mind just as I caught my first glimpse of the vineyards, where the road begins to climb, as I ascended once again to that fine village at the end of winter. Straight after a curve and a meander of the Tanaro, just after spying the stately silhouette of the tower and beyond the first hairpin bends skirting the Ovello, almost at the crest, and there, with the ebbing and flowing fog rising to reveal a stupendous panorama, images and expressions began to overlap without yet finding any precise, defined, or punctual order.

Gaja. Gaja. Gaja. Before me, a string of hills that rolled like waves of real estate. I rummaged in my memory for those words of Veronelli, the greatest food and wine gourmet, maestro of all, who, after he had effused in full-bodied and textural words on a painting by Chagall of violin players and honeymooners suspended in the air, invoked with ineffable admiration, with fulsome praise, “his Angel”: Gaja. I recalled the drawing of the winemaker who flies over the towns and fields and houses. I couldn’t vouch for its authenticity, but it was highly likely. I must have read it. It was nice to imagine it there, in that instant, because that morning it felt like I was above the clouds, especially when the first rays of sun slanted over the horizon to impale the rivers and create a crown of vibrant sparks.

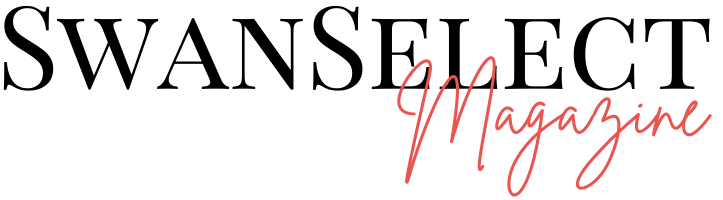

All the while, the memories accumulated. That’s how I got to know Angelo Gaja: reading, listening; and imagining, a little. It must be twenty years ago. Reading his deeds in guides and magazines, Italian and international, savouring the legend even more than the wines, through the tales of hosts, enthusiasts and restaurateurs, who every time they braced themselves to reel off the finest wines of Italy and the world, never failed to emphasise Barbaresco di Gaja. Or even just Gaja. And even that title sufficed to express all its excellence. Then you could list its crus, their names whispered like hidden desires, rare and precious: Costa Russi and Sorì Tildin, Sorì San Lorenzo, Darmagi, Sperss, and Conteisa; the whites Alteni di Brassica (I tasted an 1986 with him, the first made, with extraordinary texture, still alive and thrusting, that simply screamed Langhe, land of his origins), and Gaja & Rey.

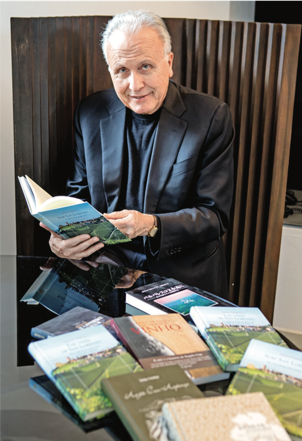

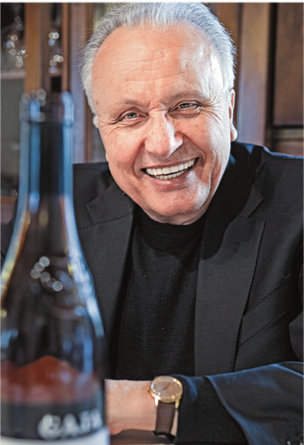

Nothing has changed. Everything evolves. Coveted and enjoyed tipples. Then and now. Eagerly caressing over and over those graceful and instantly recognisable bottles, the seal embossed on the glass, the black and white label like the greatest red wines. With unflagging enthusiasm, energy and an ability to charm that is more unique than rare, Angelo Gaja has spread the fame of Barbaresco around the world, to the most exalted tables, in the most important places. Every time I approach him I am filled with awe. When he arrives at our meeting, accompanied by his youngest son Giovanni, he is a turbine, an unstoppable stream of words and thoughts. Giovanni looks at him as one admiringly regards a father, he will stay at his side all day. And then the thoughts flow plentifully: climate change, its influence on viticulture, the Gaja team recruiting agronomists and scientists so as to remain up to date, which in this specific case means always being a step ahead. “You have to begin to describe wine not only by its organoleptic qualities but also through a whole set of aspects associated with history, politics, and the governing of the land, which I call genius loci.” Angelo Gaja begins thus, fulminating. My classical reminiscences, already aroused, suggest to me that in this expression, fine and vibrant, the concept itself of terroir is expanded to infinity. Genius Loci: Spirit, good or evil, which in pagan legend presided over the destiny of man, and also the spirit that had a city, a people, a nation under its protection. So reads the Treccani. “Wine, great wine,” – he corrects himself, I most emphatically emphasise – “is also the sum of the culture of a place. In Langa for example, we have been fortunate to have eminent political grandees who have done a lot for viticulture, though pouring their knowledge on the community.” His face lights up: “In his castle in Grinzane, Camillo Benso Count of Cavour gave form to modern Barolo thanks to the French oenologist Oudart and then he gave those teachings to all winemakers and producers.”

He continues: “Giulio Einaudi, the first President of the Republic and a wine producer, after Sunday mass in his village Dogliani, tarried among the farmers to gather and dispense advice.” Then, charting the spirit of the people of Langa with liberal impulses and a gambler’s instinct, a stream of famous characters and references issues forth. From outstanding writers like Pavese and Fenoglio to inspired entrepreneurs like Ferrero, to diverse personalities more directly linked with the wine world (Domizio Cavazza, Giacomo Morra and Arnaldo Rivera, Rena- to Ratti, Bruno Giacosa and Aldo Conterno, Domenico Clerico and Flavio Roddolo, concluding with Carlo Petrini and Luigi Veronelli), Angelo Gaja paints a multi-faceted fresco.

Again. For it also happened during the celebrations marking his winery’s 150th anniversary, when Angelo Gaja expanded the stage and seemed to take a low profile to make way for others, the noble vignaioli, and other gallant folk of Langa. The gesture was so stately that it illuminated himself, his winery, his family, and his land even more. And there was light.

Angelo Gaja dominates the stage but apparently without wishing to steal any limelight from his colleagues. He is a showman reeling off data, anecdotes and premonitions. An iconoclast: “Please, no photos in the cellar, no photos with the bottles.” He seems apparently outside time, off the grid, not in line with modern marketing and communication technologies

And yet, he is actually ahead of it, and he has his premonitions: “The Asian market, the Chinese one in particular, has essentially reached its limit for absorbing French wine, especially Bordeaux, and soon it will be the turn of Italian producers to make themselves appreciated and famous, and increase their sales.” However, the table still pays homage to Langa tradition in Trattoria Antica Torre di Barbaresco, where he is at home, and the most inspired cuisine of the region evokes other musings. “I came to this restaurant with Renè Redzepi, the Danish chef who many consider to be the best in the world, to show him how to roll the pastry for tajerin, with 22 eggyolks per kilo of flour; then using the whites and adding our ground hazelnuts to make Brutti ma Buoni biscuits, because nothing goes to waste. Redzepi was impressed.” Meanwhile we sip Barbaresco 2012, the one currently on sale, which is in fine fettle, also enlivened by a dose of nebbiolo from the Langhe crus that will not be released this vintage. His tale also takes more intimate trajectories, the childhood of his father Giovanni kept at home by his strict grandmother Clotilde all October for the harvest. “At school it was accepted that he miss a month of classes because he was particularly intelligent and caught up quickly. In that month he was also “lent” to other wineries, he moved to other villages and stayed with other families, a week here, a week there, and he especially liked going to a family in Serralunga from the area near Gabutti who treated him well: good pay and good food. When he recalls those days, the wines of Serralunga always held a particular, irresistible charm for him.