by Luca Govoni

Wine is an aphrodisiac. Many of the greats of history were convinced of this, from Plato to Charlemagne to Manet.

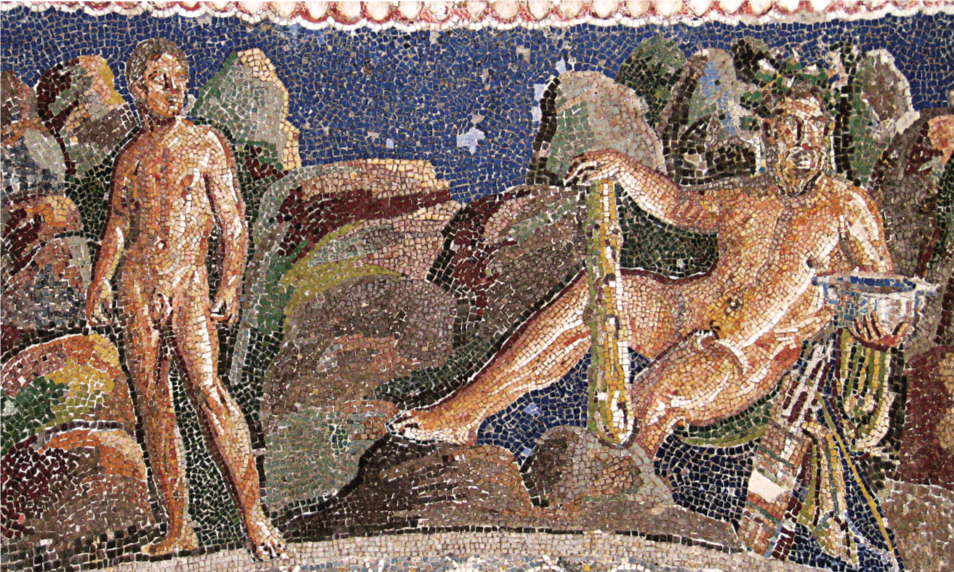

(‘Tiberius in Capri’ is a French engraving depicting the Roman emperor in Villa Jovis, situated on the peak of Mount Tiberio, in the eastern part of the island. The Roman author Svetonius narrates that Tiberius amassed a collection of Greek erotic paintings in its private halls, to provide inspiration during the frequent orgies and bacchanalia that were organized in the villa.)

“The wines were excellent, there was a certain red wine they called ‘make-sons’ which led to much facetiousness”

“Pay attention to Champagne, drink plenty of it, oh blessed ones, after lovemaking it is an excellent pick-me-up; but not more than 2 or 3 glasses before, to avoid tremendous defeats.” These are the words of the celebrated Italian food and wine critic Luigi Veronelli that conclude his little pamphlet La cucina d’Amore (The Cuisine of Love). The 21 recipes gathered in the booklet, accompanied by a pairing with a wine or peremptory advice on the taste, are the mirror of the bibliophile activity with which the author tackles various aspects of the gastronomy and oenology of Italy. Whether it is a potage of capon’s testicles recovered from the Opera by Bartolomeo Scappi to be served with a Tocai, rack of lamb Dugazon-style accompanied by a wine from Valpantena, Carnacina-style artichoke stems and a fava bean potage, or a clear soupe de coupigny to be paired with a Cortese, the connecting thread is the intrinsic relationship between food, beverages and love in a dual capacity. The relationship is thousands of years old. It was commended by Plato in his Laws, where he describes as “great fundamental appetites” specifically eating, drinking, and procreating.

But forget about the novelty! It matters little whether it was an apple, a fig, a pomegranate or a grape; the lewd sense of nudity appeared only after the act of eating, and thus it was that Adam and Eve “consuerunt folia ficus et fecerunt sibi perizomata”. The extensive reference literature would dishearten any libidinous reader or intelligent editorialist, but Veronelli eagerly tackles the topic, choosing some recipes and some beverages with the decisive firmness of an adult who solicits the malice of the reader, but one who, placing himself before the wealth of information on the subject, is certainly aware that his precise choice is gastronomically and temporally accessible. In the end, though, there is no such thing as erotic cuisine and wine. There may well be aphrodisiac cuisine and food, and aphrodisiac wines, as certain food generates sexual arousal and some wines produce libido or reduce inhibitions.

At this point, Apuleius reminds us that “wine is enough to conquer the cowardice of decency, and to put power in pleasure”. Thus we grasp and justify the fact that the history of food and wine abounds in allusive references to the two worlds clearly defined as lust and gluttony. How to make wine to restore youthful vigour in old age is recounted by medieval monastic medicine, which suggests adding fennel seeds to red wine and sounds like a modern miracle cure. Viper wine, wine in which an entire viper was drowned, apparently held miraculous powers. Piment wine, the rosé wine drunk in France in the time of Charlemagne was said to have aphrodisiac properties. And vin herbé, or the aromatized wine that probably caused Isolde to fall in love with Tristan, was certainly aphrodisiac.

On the other hand, Casanova must have had a few tricks up his sleeve, too, as it is hard to believe that he confined himself to using hot chocolate, as purported by Savarin, attributing divine powers to the beverage consumed in his Republic of Venice, who for all his expertise in the administration of exotic drinks, is somewhat naive. “The wines were excellent, there was a certain red wine they called ‘make-sons’, which led to much licentiousness”, could have countered Goldoni, with innocent, not unprepared competence. And how can we not believe that certain kings, and certain lords, villains and monks gathered with the perseverance of dutiful scribes all sorts of spices or wines, the use of which would truly have helped the act of love, through who knows what placebo effect. That said, the use of scientific methods, considered exact in the context of the era, allowed the spread of beliefs and medical-loving recipes for rich and poor. The former paid the physicians, and the latter enjoyed the vice of food and wine, which gave them psychological gratification against the fear of hunger and thirst.

For example, Tiberius’ villa in Capri seems to have been one of those palaces of eros desired by the emperor for his derision. Frescoes, paintings and landscapes alluded to lovemaking, and guests, probably dazzled by slight presbyopia clouding their eyes, let them- selves go to the point where they no longer distinguished either familiar, daily objects or themselves. Obviously the legendary Falerno flavoured with spices and cheese flowed freely. In his essay The ‘sex’ appetite: culinary metaphors and the rhetoric of the intimate, the linguist Massimo Arcangeli recounts that culinary metaphors are a concrete example of the proximity of the world of food and drink to the world of sex, as in the case of the resemblance in shape and consistency of the male attributes, or that which is associated with the taste of the female organ. Endocrinology, for its part, has already demonstrated that the need for food and the sexual desires are subject to control by the same hormones, while the neurosciences certify that these hormones are localized in the same area of the brain, so that the sexual appetite, if not satisfied, can be assuaged by the consumption of food. “The psychic force that lies at the base of the sexual instinct is equal to the force of hunger, and similar to willpower or other similar tendencies of the ego”, Freud would say, giving no opportunity to reply.

And there is no point in denying or looking for excuses: the act itself of the child taking milk from its mother’s breast is the first indissoluble link between the experience of food and the excitation that will allow education and which will lead us to adulthood. Manet knew this well: at the idea of depicting a frugal occasion like a snack, he uses no colour other than that suitable for painting the nude bodies of women and then men, once again documenting that golden combination that today, with the best will in the world, we cannot keep quiet...

And if, again paraphrasing the magistrate Brillat-Savarin, “wine is the most agreeable of beverages, whether we owe it to Noah who planted the first vineyard, or to Bacchus, who first pressed the juice from the grape, given since the infancy of the world”, then it is certain, concludes Luigi Veronelli, that “wine chosen with loving care and skilled taste is a necessary complement of every endgame. [...] I do not agree with Curnonsky, who ostracised white wines from “matters of the heart”. I would counter: not just whites; when red would be fine by itself. A common rule: they should be young, light, velvety and fragrant. They should not weigh you down, but enliven you. Do not fall into the trap of drinking too much: the effect would be negative, the opposite of what you desire.”