by Luca Govoni

The world of the dithyrams of Francesco Redi, lyrical compositions that extol inebriation brought by wine, in the name of fantasy and “doing whatever you like”

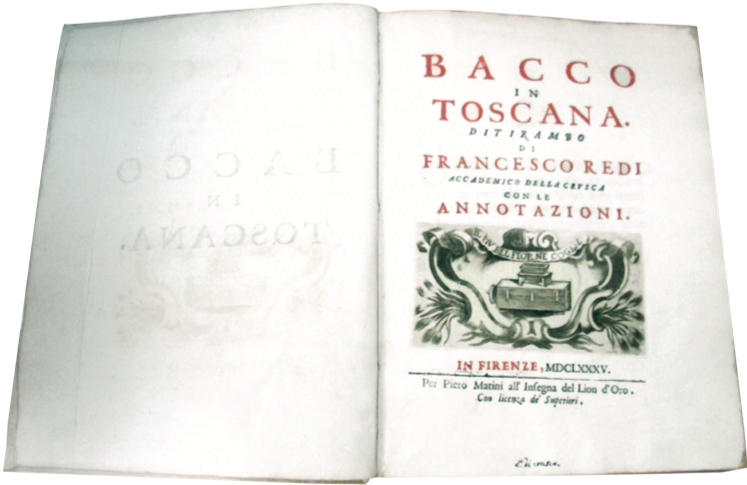

“If of the grape the lovable blood / does not refresh the veins every hour, / then this life is too fleeting, / too short, and always in penury,” recited Francesco Redi in the name of Bacchus. It was 12 September 1666 when the doctor and naturalist from Arezzo declaimed for the first time the verses of the festive dithyramb Bacchus in Tuscany, an official ‘cicalata’ (rigmarole) in verse, before the Accademici della Crus- ca Italian philological and linguistic society, in the presence of princes Leopoldo and Mattias de’ Medici. The ‘stravizzo’, the collegial lunch organized twice a year, was a solemn supper that was held on the occasion of the election of new members and academic offices, and was punctuated by readings of cicalate, or ‘comical com- positions, to make one laugh’. “And stravizzo is eating, which together make conversations cheery,” says the dictionary of the Accademici della Crusca.

So, between one course and the next, between veal and sweetbread pie, turkey braised in wine and pheasants adorned with their feathers, the scholar Redi named 57 Tuscan and other Italian wines of quality, finally celebrating Montepulciano, which by the highest decree, is proclaimed ‘king of every wine’. The dithyrambs, lyrical compositions that extol inebriation from wine and express joie de vivre, gave historical continuity to the choral lyrical poetry of classical Greek literature, which celebrated Dionysus and his cult by bringing together poetry, music and dance. And yet, Francesco Redi’s rant in front of a learned audience in an explicitly ceremonial context is very similar to the desire for social escapism that man has always needed to demonstrate in widely diverse circumstances and contexts.

In effect, bearing in mind the context and not reducing the Bacchus in Tuscany composition to a relationship between man and the environment in terms of productivity, expressed by Redi in the enumeration of fine wines, a message can be seen that seems to have already been read, seen or experienced somewhere. There is a glimpse of a Dionysian world, not by chance, there where you can do what you want, to paraphrase Virgil in Dante. Hence, between a Claretto, a Trebbiano and a Colombano, Redi declaims: “I would sooner drink poison / than a glass, though it were full / of bitter and offensive coffee”, and, “Drink English cider / who would soon be underground”, or, “squalid cervoiseale”. So it seems accepted that fantasy and imagination may orient us towards a utopian and uchronic space-time dimension where “you can do whatever you want”. It seems permissible to state publicly and it recalls those topsy-turvy worlds wonderfully celebrated in paintings, etchings and writings.

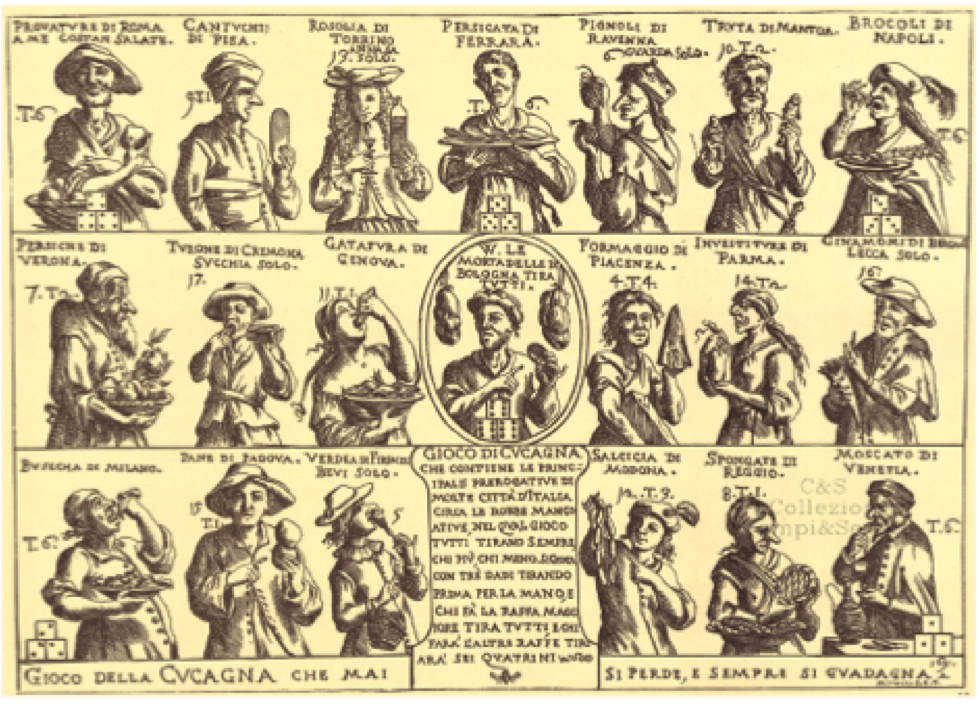

The great semantic field of the world turned upside-down, of the “you can do whatever you want”, could include the Coena Cypriani, which in fact confuses the mind of the apprentice Adso in The Name of the Rose, the worlds of Frigia and Lidia described in the Euripidean Baccananti, the places of opulence described in Crates’ Wild Beasts, where thrushes fly already cooked into men’s mouths, or in Cratinus’ Ploutoi, where they play dice with wheat loaves. And what of the Land of Plenty or the etchings of Giuseppe Maria Mitelli from Bologna, a contemporary of Francesco Redi? The artist carved puzzles, riddles and anagrams refer- ring to food and Italian specialities, which routinely became prizes: “The principal prerogatives of many Italian cities regarding things to eat”. And then there are the Burlesque Operas of Francesco Berni, Pietro Aretino, Ludovico Dolce, Francesco Sansovino, Girolamo Benivieni, Nicolò Martelli and several other authors. The Collection of Toasts compiled by Dr. Buontempone and published in 1878 gathers together a large number of toasts to be used on the occasion of solemn symposiums, cheerful suppers and ‘companionable pig-outs’: “Drinking is joy, drinking is life: / in wine swims every happiness; / Bacchus tames every torment; / Bacchus relieves every pain. Long live Bacchus! Long live Love!”

Michail Bachtin, analyzing the work of Rabelais in relation to popular culture and to the narrative defined as carnivalesque, showed that “even the oldest convivial images that have come down to us are profoundly conscious, intentional, philosophical, rich in values and living bonds with all the surrounding context, and are not at all the walking dead of now-forgotten worldviews. In the system of folk festivals, they have been developed and renewed over the course of thousands of years, and have continued to have conscious and artistically productive existence”.

In fact, the greasy pole is still seen in village festivities, certifying its transcendental meaning: the tree rises from the earth to the sky, and its heavenly branches are filled with delicious ripe and blessed fruit. The Tree of Plenty, which became the greasy pole, the topsy-turvy world, Mitelli’s game of plenty and Redi’s dithyrambs highlight a social limit and at the same time provide the means to cross it. Hence the setting down in prose of every vice or virtue, the mocking in a witty or moralizing way, the representing of the land of idleness, of freedom and of youth, and the celebrating of abundance and emancipation and so on is nothing other than belonging to a human legacy ius sanguinis that thumbs its nose at moral confines and social hierarchies. A sort of right to gypsy-dancing to the strains of “Fine daughter of love, a slave I am to your charms; with one word, one word only, all my troubles you can console”. With all due respect to moralists.