by Andrea Grignaffini photos by Lorenzo Cotrozzi

Oriental cuisine uncovers its potential with rosé wines, which nicely complement the sweet-and-sour and spicy notes of its dishes, and reveal its unexpected health benefits.

Still or sparkling, it breaks the moulds imposed by the dichotomy between red and white

The phenomenon was enough to induce the French, who have always been ahead of the crowd in matters of wine, to create a special organization with the sole task of monitoring the situation. We are speaking about the rapid increase in the global consumption of rosé wine, official data for which is provided for us every year by the assiduous Observatoire de l’Economie du Rosé curated by the Conseil Interprofessionnel des Vins de Provence. Coming to the heart of the matter, in the two years 2011-2012 alone, consumption of rosé jumped 13.38%, a dramatic surge of approximately 16 million hectolitres, which is a figure that gives credence to the forecast relating to the continuous increase in years to come. To what do we owe this sudden explosion in the consumption of rosé? It may be nothing less than an evolution in taste. Because, to those who can comprehend it, rosé is a transgender wine. This is not only on account of the pigment that characterizes it, but also because, according to the directives of the European Union, it is also the felicitous outcome of the fermentation of grey grapes, as is the case with grenache gris or pinot gris, or of macerations with grape skins that are poor in colouring material such as, for example, pinot noir and poulsard. Rosé is the outcome of a procedure whose agent, the grape, takes on a new colour but with an ancient reflection.To what do we owe this sudden explosion in the consumption of rosé? It may be nothing less than an evolution in taste. Because, to those who can comprehend it, rosé is a transgender wine. This is not only on account of the pigment that characterizes it, but also because, according to the directives of the European Union, it is also the felicitous outcome of the fermentation of grey grapes, as is the case with grenache gris or pinot gris, or of macerations with grape skins that are poor in colouring material such as, for example, pinot noir and poulsard.

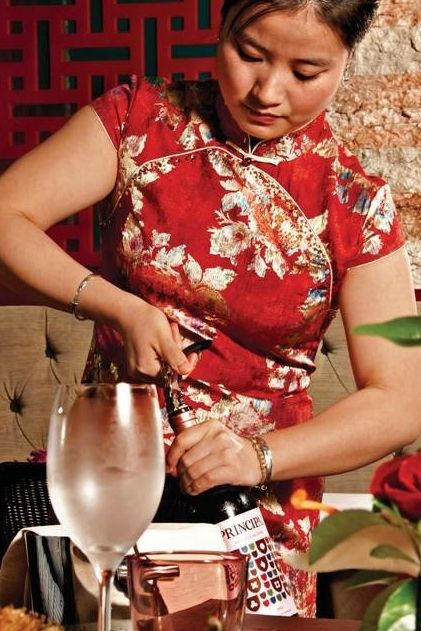

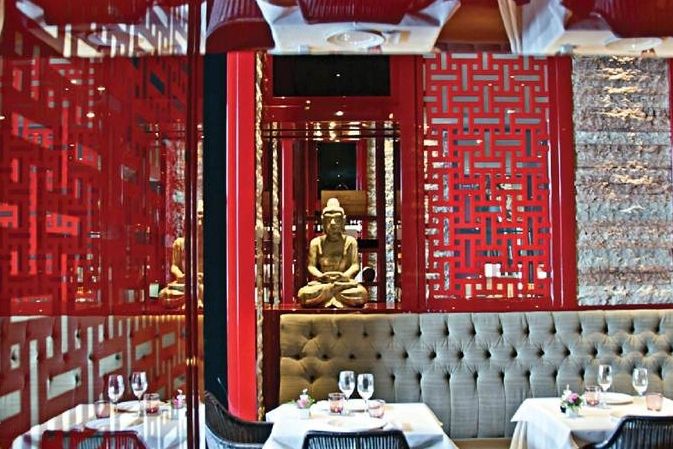

Rosé is the outcome of a procedure whose agent, the grape, takes on a new colour but with an ancient reflection. As such, the wine obtained throws open the doors to a world that is still unexplored, departing from the etiquette that has been instituted as a function of the dichotomy surrounding the red and white poles and distancing itself from, among other things, the principle of seasonality, to which even the best-informed tend to associate the consumption and the occasion of wine. Farewell, then, to the sterility of generalizations such as “red in winter/white in summer”, “white by day/red at night”, “white with fish/red with meat” and so on. In spite, then, of the popularity that rosé appears to be enjoying in this moment in history, we can state with almost total confidence that its ascent will be continuous and inexorable. Its strength? The transversal nature it has by virtue of the fact that it is neither white nor red: popular and worldly, to be sure, but not trendy, as might be suggested by a tendentious reading of the Observatoire data, which actually affirm its leadership in those countries that have recently had to come to terms with the proliferation of alternative realities, cosmopolitan realities, of differing modes of existence. Hybridization, also in culinary matters, is thus the key that allows us to confidently join in the game brought into play by the future, which rosé is certainly winning. Oriental cuisine, for example, reveals its potential to rosé, which has demonstrated its ability to harmonize with diverse flavours, such as sweet and sour, but also accepting spiciness with notes of greater or lesser pungency, more or less pronounced aromatic nuances, herbaceous, floral or fruity aromas, and even bitterish aftertastes, which seem to be enjoying new interpretation possibilities thanks to the mellow tannins and the crisp acidity of rosé, whose propensity for the exotic is shown in the most striking evidence during the course of dinner at the excellent and stylish Bon Wei Restaurant in Milan, an exclusive eatery that is the best of the many Chinese restaurants that have opened in the Italian capital over the years, located in the Paolo Sarpi district of Milan, where most of the Chinese community live. We paired the dishes with Principal Rosé Tete de Cuvée 2010 Barriada Doc Colinas de São Lourenço, made from pinot noir grapes in purity: this Portuguese rosé was tasted before by the Italian edition of “Spirito diVino” during a tasting of international rosés, which it won with a score of 92/100.

With its fruity notes, refreshing acidity of citrus fruits and blackcur-rants, and mineral nuances, this wine nicely accompanied the slices of abalone sautéed with onion and crispy asparagus, actually empha-sizing the unexpected and gratifying mushroomy aroma and reaching citric harmony with the slivers of ginger. It was also a good match for the glossy, succulent chunks of turbot sautéed with carrot and slightly garlicky asparagus. Here, the rosé tamed the ‘seabed’ notes of the fish and the ‘earthy’ ones of the vegetables, exalting the mineral edge of the asparagus and bringing a hint of acidity to the sweetness of the carrot. With its elegant bubbles, notes of orange, grapefruit and strawberry, faint hints of toasting and fine acidity, Colinas Spumante Brut 2009 De São Lourenço delicately smoothed the gamey flavour of the morsels of glazed duck encased like a cannoncino in a kind of tortilla, revealing the freshness of the cucumber and the mineral side of the leeks in the stuffing. It went perfectly, too, with the delicious slices of stewed beef enlivened with strips of ginger, whose intrinsic spiciness exalted the effervescence of the bubbles, creating a sort of citrusy tourbillon that refreshed the palate and, impertinently, further stimulated the appetite, for a night ever more in pink.

A winning wine because it extends a warm welcome to culinary alternatives

ROSÉ WINE AND CHINESE CUISINE: a healthy synergic combination

In the last twenty years, numerous studies have highlighted a significant reduction in the incidence of cardiovascular diseases associated with a moderate consumption of wine, with particular reference to the drinking of red wine. The difference between red wine and white lies mainly in the fact that the former contains a higher concentration of polyphenol compounds. In fact, the concentration of these molecules in red wine is around 20 times greater than that found in white wine.

However, among the substances contained in wine that have beneficial effects on our organism, there is also resveratrol, whose activities at a clinical level have been scientifically documented since the early ‘90s, and which range from cancer prevention to protecting the heart and brain, and from the reduction of age-related diseases to decreasing inflammatory states, diabetes, and obesity. As well as being contained in red wines, this substance is also present in considerable quantities in rosé wine, in particular that obtained from Pinot noir grapes. In grapes, resveratrol is found primarily in the skin, and in muscadine grapes, also in the seeds. The amount found in grape skins also varies with the grape cultivar, its geographic origin, and exposure to fungal infection. The amount of fermentation time a wine spends in contact with grape skins is an important determinant of its resveratrol con tent. For these reasons, red and rosé wines generally contain more resveratrol than white, precisely because of the winemaking technique, which entails maceration on the skins, with the consequent extraction of the substance.

A recent study by the British University of Reading published in the scientific magazine «Antioxidants & Redox Signaling» sho-wed that regularly drinking sparkling rosé produced from Pinot Noir and Pinot Meunier grapes determines an improvement in spatial memory and wards off the onset of dementia or cognitive impairment, including Alzheimer’s. It is highly likely that this action is also to be traced to antioxidant polyphenol substan-ces contained in wine. Rosé wines also have a synergically in conferring their health benefits when they are combined with Chinese cuisine, also through the warm reception it reserves for these fusions by permitting them access to our tables and, in so doing, helping us to normalize them. Among the chief virtues of Chinese cooking, one important aspect must surely be attributed to a utensil used in the preparation of food: the Wok, the tradi-tional and versatile round-bottomed cooking vessel originating from Guangdong Province in China.

This form and method of cooking makes it possible to use very little oil and fat, and additionally, the fact that the food is sautéed over a high flame allows it to be cooked faster and preserve al-most all its nutritional properties. And we must not ignore the fact that Chinese cookery also features many steamed dishes.

It improves spatial memory and wards off the onset of dementia, including Alzheimer’s

This cooking method has several advantages: as with the Wok, it does not require the addition of oils or fats and it preserves the nutritional characteristics and the taste of the food. Soya and ginger, widely used in Chinese cuisine, also have beneficial effects on the body. Numerous studies have highlighted the benefits of soya, thanks to the abundance of isoflavones, which protect against the risk of developing tumours, coronary disease and osteoporosis, while ginger aids digestion and combats nausea. In China the rhizome is also used as a cold remedy. Finally, it is our duty to make mention of Chinese Restaurant Syndrome, which was described for the first time in 1968.

This syndrome is characterized by an annoying headache, weakness, asthma, and reddening of the face, and it usually erupts half an hour after eating in a Chinese restaurant. It is reputed to be caused by the glutamate used in several dishes of Chinese cuisine as a flavour enhancer. Actually, the issue is rather hotly debated and some researchers have even called the very existence of this syndrome into question. Glutamic acid is, in fact, also present in high concentration in our Parmigiano Reggiano and seasoned Prosciutto. In short, those who have problems after eating in a Chinese restaurant should perhaps blame an excess of salt, or poor quality ingredients, or too much fried or greasy food, or something else, but not the glutamate!

Dr. Stefano Reggiani

Medical Director of Hesperia Hospital in Modena, Italy

Rosé wine finds a synergic ally in conferring benefits to health when it is combined with Chinese cuisine: in particular, cooking food in the wok (the traditional round-bottomed pan, generally made of iron or cast iron) allows the use of oil to be limited and preserves all the food’s nutritional properties.